Information overload, and its attendant pathologies of information, wrongly thought to be a product of the digital age, of social media, and the like, have received much comment in recent years. With attention focused on the ways in which the digital environment removes many of the informational frictions in the communication chain, the long history of complaints against overload can easily be overlooked, a point Lyn Robinson and I made in a review of the concept of overload.

A recent article by Jan Stodolnik repeats and amplifies the point that fears about attention spans and lack of focus are as old as writing itself. A number of examples are given, some familiar and some new: the ancient Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger complains that “the multitude of books is a distraction”; Zhi Xi , the Chinese philosopher of the 12th century, regrets that “the reason people today read sloppily is that there are a great many printed texts”; the 14th century Italian poet Petrach laments that the reading of many books is not nourishing the mind, but killing it and burying it with the weight of things; the Renaissance scholar Erasmus feels mobbed by swarms of new books; and Conrad Gessner, the pioneering 16th century bibliographer, worries that readers will rely on the new technology of indexes, rather than reading the works themselves. To bring the story up to more modern, albeit pre-digital, times, we might add the comments of Thomas Huxley at the 1885 anniversary meeting of the Royal Society: “It has become impossible for any man to keep pace with the progress of the whole of any important branch of science. If he were to attempt to do so, his mental faculties would be crushed by the multitude of journals and of voluminous monographs which a too fertile press casts upon him”.

Modern concerns about the distraction of digital information and social media are not new, Stodolnik reminds us; we seem throughout history to have longed for a return to a “past age of properly managed attention and memory”. This past age seems always to be a dimly defined and nostalgically perceived time, shortly before our own generation, whenever that generation may be.

To add to the confusion, as Stodolnik points out, for as long as the problem has been recognised, solutions have been proposed. Sometimes they are contradictory. For example, the reading of lengthy novels, now proposed as a solution to the distractions of social media by present-day writers such as Johann Hari, was in earlier times regarded as a part of the problem of distraction from serious thought, by Walter Benjamin among others

.

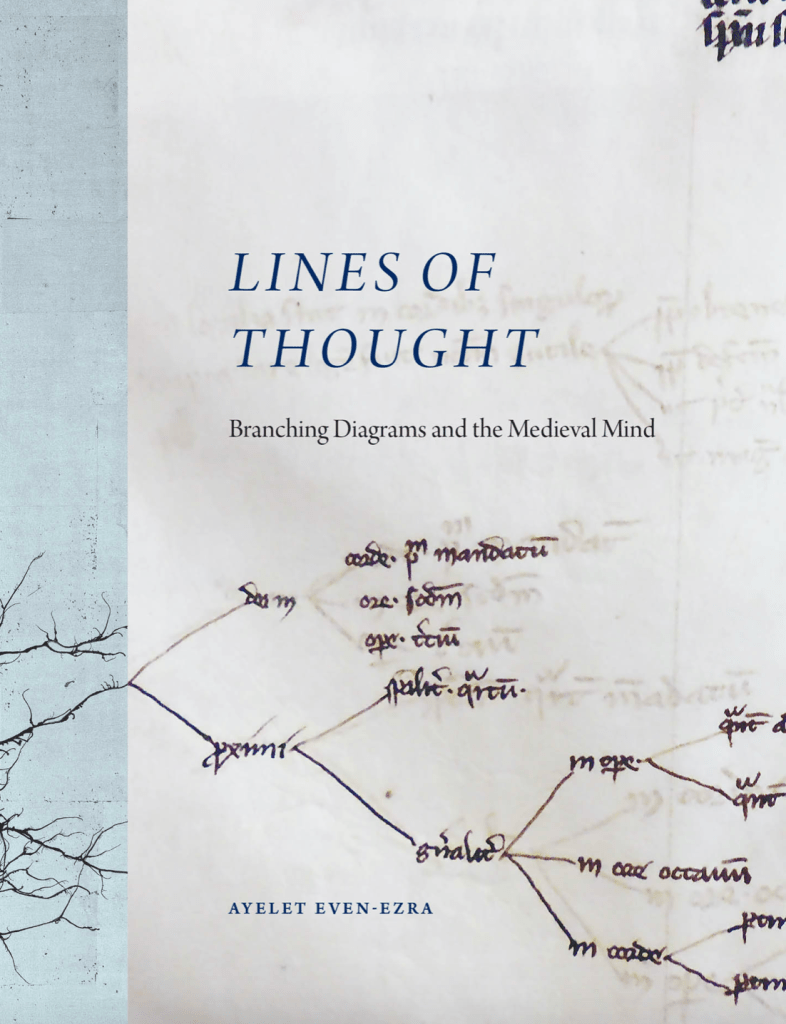

Stodolnik goes into some detail about an interesting and early solution; the branching diagrams of concepts which appear in many medieval manuscripts. These diagrams are analysed in detail by Ayelet Even-Ezra in her book Lines of Thought: Branching Diagrams and the Medieval Mind. They can be seen as enabling the repackaging of information and ideas in formal patterns, allowing an appreciation of the broader context of the details, and hence as another early antidote to overload.

And yes, another article discussing information overload may seem a bit of an irony, but Srodolnik’s is worth reading for its nuanced take on how our use of information and our thought process interact and influence each other, and how they have always done so.