In a post of some years back, I mused on how rocks and minerals could be regarded as documents, conveying information, and as informational entities in their own right, and drew attention to the way in which their documentary/informational status had been discussed by a variety of thinkers, from Suzanne Briet to Luciano Floridi.

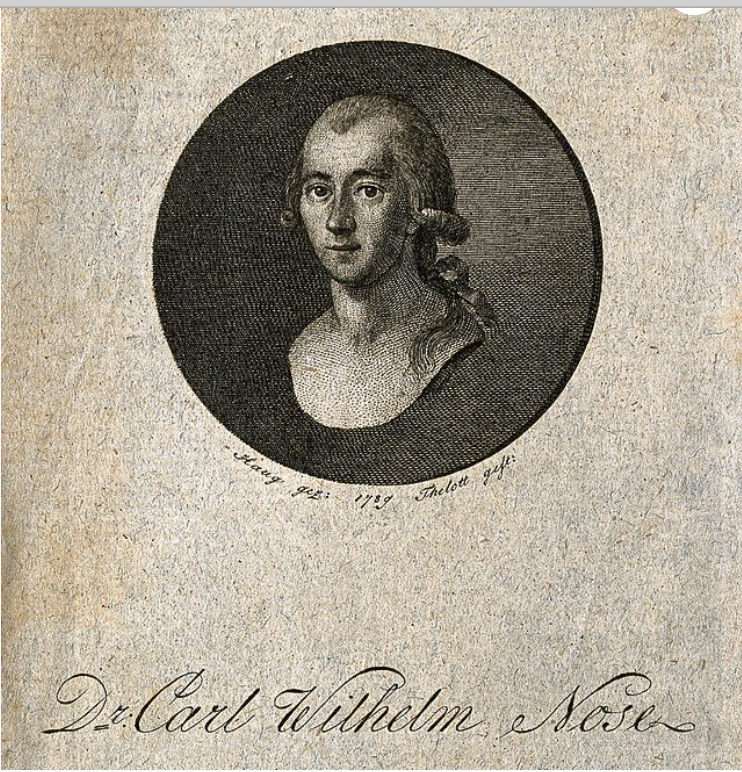

Some these issues are analysed in one specific context, in a recent paper by Angela Strauß on “Rock value. Scientific and economic conditions for collecting minerals in the early nineteenth century”. (Journal of the History of Collections vol. 35 no. 1 (2023) pp. 77–90). This paper focuses on the German physician and mineralogist Carl Wilhelm Nose (1753–1835), and his exploration and collection of the rocks of the Siebengebirge mountain range. Nose donated many of his specimens to individuals and institutions, at a time when the natural history museum collection as we understand it today was being established

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0. Wikimedia.

As well as details of networks and collecting practices of Nose and his equivalents in Germany and in other countries, and of economic issues in the valuation of specimens and collections, the paper takes an interesting collection-centric viewpoint on “the transformation by means of which natural things became objects of knowledge”. Although Strauß does not frame the analysis in explicit terms of document theory, and does cite any authors from the information sciences, the discussion is suffused with the ideas of documentation, as when Strauß notes that Nose and other mineralogists “literally removed an object from its natural habitat and embedded it in their own abstract order to create or visualize scientific ideas”. In this case, a main scientific idea is the process by which the rocks of the earth took their present form, through processes such as vulcanism and weathering, illustrated by Nose and his followers by the co-location of similar specimens. Such organisation of collections was the first step toward the variety of classifications of minerals extant today.

Collecting and classifying natural history materials – plants and animals, rocks and minerals – has been a major, and to a degree unrecognised, influence on the sciences of information and documentation, and historical studies such as this are very much to be welcomed. The information sciences would do well to pay more attention to the history of collections and collecting.