While reading Dava Sobel‘s fascinating study of the life and work of Marie Curie, I was intrigued by a passing mention of something I had not known before: Curie’s involvement in the early attempts a bibliographical control of scientific publications.

Sobel tells us that “July 1922 found Marie in Cavalaire [a Riviera coastal resort] for a brief rest before the daunting first meeting of the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation [ICIC], to be held in Genea in early August … Marie emerged from the Geneva deliberations with membership in two subcommittees, one devoted to securing scholarships and grants for researchers, and the other to creating an annotated – and constantly updated – bibliography of articles from scientific publications the world over” (pp. 196-7). But by 1933 “Marie had to admit that her years of service with the League’s International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation had borne very little fruit. None of her pet projects … had been realized. Even her major goal of creating an annotated international bibliography of research in specific disciplines was stalled for lack of enthusiasm. The relevant government agencies, publishers, and professional societies seemed unwilling to relinquish their own traditions, customs, and tastes for the greater good” (pp 250-251).

I had heard of the ICIC, but not of Curie’s involvement with it. As that is all that Sobell says about this, I wondered if anything more had been written. Of course it had, and Peter Lor’s detailed study tells the story in a paper in IFLA Journal (an open access repository version is here).

And a somewhat depressing story it is. One of international documentation projects espoused by the League of Nations, towards a “new information order” for the interwar years as Daniel Laqua terms it, the ICIC’s Subcommittee for Science and Bibliography was to “facilitate international co-operation as regards bibliography, to examine the question of a legally recognised international depot for publications, etc”. Its membership included some very distinguished scientists, with Curie by no means the only Nobel-winning member, as well as leading European librarians. By 1928 Curie chaired the sub-committee.

The committee had ambitious aims, towards the creation of a universal international library, through legal deposit, bibliographical control, and interlending. It addressed many specific issues including: avoiding duplication between scientific abstracting and indexing services; how to deal with works published in less-spoken languages (especially in newly independent countries such as Poland and Czechoslovakia); international lending of books and manuscripts; tables of constants; the standardisation of periodical formats; microphotography; national union catalogues of periodicals; standardisation of linguistic terms; conservation of printed works and manuscripts, with particular concern about the quality of paper and ink; publication of a guide to national information centres for interlibrary lending; and information sharing among large libraries about purchases of foreign books.

Alas, these ideals were compromised by the bureaucratic committee and sub-committee of the League of Nations, by the complexity of the many stakeholders in a multinational and multilingual environment (especially without digital resources or electronic communication), and by fractious relations with potential collaborators due to history and personality. Particularly unfortunate were the somewhat adversarial relations developed between the subcommittee and Paul Otlet and Henri Lafontaine of the International Institute for Documentation (later renamed the International Institute for Bibliography), who were never invited to join the sub-committee.

These problems were not unique to this group, and in 1930, the League abolished all its sub-committees. The remit of the Science and Bibliography sub-committee was, to an extent, continued by the ICIC’s Committee of Library Experts, and ultimately by UNESCO and IFLA.

While the results of the sub-committee’s activities seem modest, when set against the initial ambitious aims, it is worth noting that the proposals put forward by Marie Curie in particular were far-sighted, even if they could not be achieved in the technological and socio-political environment of the 1920s. A particular concern, which Lor calls a “hobby horse” of hers, was the standardisation of format for articles in scientific journals. Then she proposed an international system of ‘dockets’, cards with abstracts of journal articles prepared to a common format and standard by editors of scientific journals, which would be submitted to a central agency to create an international index of scientific articles. (This proposal particularly irritated Otlet, who saw it as ignoring his work towards a universal bibliography.) To complement this, she proposed that national legal deposit system be expanded internationally, to create a universal library of all the world’s scientific journals.

These ideas were way ahead of their time, and still have not been fully realised today, though, like Otlet’s, they influenced later developments. We should, I think, add Marie Curie to the list of information visionaries, who foresaw how the information environment could be, before the technologies to enable the vision were available.

Reading

Daniel Laqua. Intellectual exchange and the new information order of the interwar years: the British Society for International Bibliography, 1927-1937. Library Trends, 213, 62(2), 465-477.

Peter Lor. Librarianship and bibliography in the international arena: The Subcommittee for Bibliography of the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation 1922–1930. IFLA Journal, 2024, 50(4), 755–768.

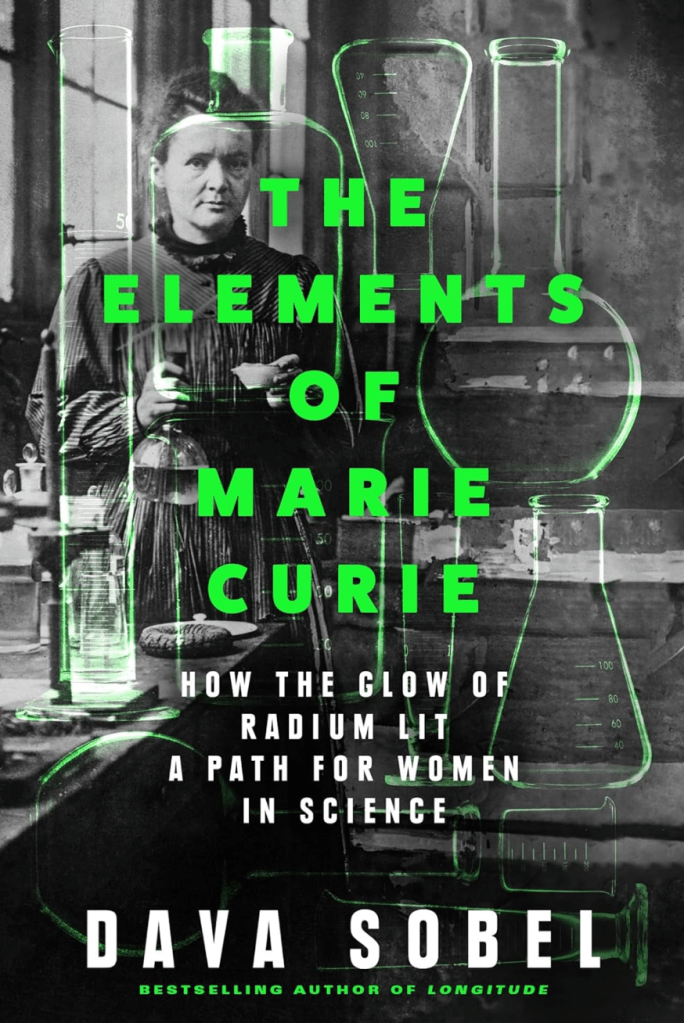

Dava Sobel. The elements of Marie Curie. London, Fourth Estate, 2024